by Betsy McCully, Nov. 12, 2018

Updated August 25, 2023

How Our Coastal Wetlands Evolved

In the shallow waters of estuaries, sediments eroded by tidal action are deposited along the shores, building mudflats where cordgrasses take root and grow into coastal marshes, or wetlands. The marshes may grow seaward wherever fresh sediments have been deposited or landward in response to sea-level rise.

The wetlands that fringe the shores of the New York region and the nutrient-rich estuarial waters have supported a diversity of species for thousands of years, including human.

Looking closely into the green world of cordgrasses, you can see marsh periwinkles graze on the algae that coats the lower stems of cordgrass. Salt marsh snails forage on dead cordgrasses. Along the creek edges, you may see ribbed mussels anchored in the peat, attaching themselves to cordgrass roots with strong threads called byssus, in effect binding the marsh together. At high tide, they filter the water for plankton, detritus, and bacteria; a large group in a marsh can filter all the water flowing through in a single tidal cycle. In creek shallows, little fish mill about, including killifish, Atlantic silversides, sheepshead minnow, and sticklebacks. They eat snails, insect larvae, algae, and detritus. In creek banks, you may observe the little burrows excavated by fiddler crabs, using their supersized claws to dig out pellets of sand and mud that they stack beside the burrow openings.

All these smaller denizens of the marsh provide food for larger creatures — turtles, raccoons, muskrats, birds. The Diamondback Terrapin, for instance, is the only reptile whose exclusive habitat is the salt marsh, and our only beach-nesting turtle. Numerous birds — migrants on the Atlantic Flyway as well as summer breeders and year-round residents — feed, mate, and nest in these marshes. These include waders like the herons, egrets, and glossy ibis that feed in the marshy shallows and mudflats, and thousands of migratory shorebirds that stop over in the marshes to refuel. Less conspicuous than the waders and shorebirds are several more secretive avian species: the endangered salt marsh sparrow and seaside sparrow, both of which are salt marsh specialists, and the elusive clapper rail, which secretes itself in the grasses, and is more easily heard than seen.

How Our Coastal Wetlands Became Degraded

Over the last few centuries, since European colonization and settlement, the wetlands have been severely degraded by pollution, development, and now climate change. No sooner had the Dutch colonized the region than they began to drain and fill marshes, just as they had done in the Netherlands, also known as the Low Countries because they were below sea level. The Dutch prided themselves on their land reclamation skills. In New Netherland, the Dutch filled in marshes and built out their shorelines to create more taxable real estate and accommodate a growing city. Dutch farmers diked and drained marshes to create pasture for their cattle. Those pockets of marsh remaining were polluted by human wastes and garbage. The practice of draining, filling, polluting and trashing wetlands, as well as building right over them, has continued from colonial time to the present. New York’s original wetlands have been reduced by nearly 90 percent.

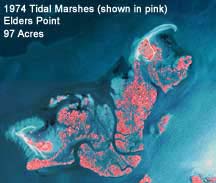

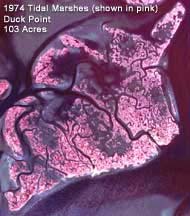

Today, rising sea levels are threatening the marshes. Historically, marsh islands and coastal marshes were able to migrate landward in response to sea level rise, but today hard shoreline development prevents this natural process from happening. Marshes are simply being drowned.

How Our Coastal Wetlands Are Being Restored

Restoration efforts began with the passage of the Clean Water Act of 1972, followed by the Tidal Wetlands Act of 1973. Healthy wetlands depend on healthy estuaries and vice versa. Together they support the fisheries that we depend on.

In May, 2012, New York City published a document outlining their “wetlands strategy” as part of Mayor Bloomberg’s PlaNYC. The authors of the document estimated that the wetlands of New York City — most extensive in Jamaica Bay, the shores of Staten Island, and around Long Island Sound — covered between 5,600 and 10,000 acres, representing a decline of 85 percent of the city’s coastal wetlands over the course of the twentieth century. Their specific goal, worked out with state and federal agencies, was “to restore or create over 146 acres of wetlands.” Already, the city (the Parks Department and the Department of Environmental Protection) had acquired 625 acres on Staten Island over the previous ten years. The goal was based on the principle of “no net loss of wetlands,” which accords with federal guidelines established in the 1980s. But they went beyond the stated quantitative target “to improve the quality of the city’s remaining wetlands and maximize their ecological functions to the greatest extent possible.” To that end, the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation (DPR) was restoring White Island, in Jamaica Bay, “through shoreline stabilization, invasive species removal, and plantings of marsh grasses,” and 22 acres of wetland and coastal grassland at Gerritsen Creek.

The New Jersey Meadowlands: A Case in Point

An example of a still-vast wetland that has been severely degraded is the New Jersey Meadowlands. It serves to encapsulate the story of decline, degradation, and restoration of our wetlands.

Once a glacial lake, this coastal plain wetland at one time covered 19,730 acres along the Hackensack River. Comprised of salt and fresh marshes and an extensive Atlantic White Cedar forest, the ecosystem supported thousands of species, including human hunter-gatherers who harvested shellfish and hunted birds and small game. When the European settlers arrived, they filled, dredged, and diked wetlands to farm. They also harvested white cedars for their valuable wood, deforesting it by the late 1890s. By the twentieth century the Meadowlands had become a dumping ground for toxic waste and garbage. Today, 1,600 acres are landfill, and mercury has leached into its channels and creek beds.

Cleanup efforts began in the 1970s, when developers and environmental groups reached a compromise. The Hackensack Meadowlands Conservation and Development Commission, a state agency established in 1969 to centralize authority over the region, has requested developers to restore portions of the wetland in exchange for developing other parts of it. The Meadowlands sports complex was built in 1974 on 750 acres of the wetlands, and permits for filling and develop 32 additional acres were granted by the Army Corps of Engineers between 1977 and 1997. In 1982, the DeKorte Environmental Center was opened with preserved wetland habitat. In 1999, the state legislature approved the formation of the Meadowlands Conservation Trust to acquire and preserve more “environmentally valuable land.” Since then, 8400 acres of the ancient wetlands ecosystem have been restored.

Of course, these are mere fragments of the original tens of thousands of acres of wetlands that fringed our shores.

Unfortunately, under the administration of Chris Christie, governor of New Jersey, the restoration project became threatened. In 2015, Christie in effect hijacked the Meadowlands Commission by bringing it under the purview of the Meadowlands Sports and Exposition Authority. He diverted the entire restoration budget of the Meadowlands Conservation Trust — $3 million — to a general state fund in late 2017, starving the agency of the funds needed to go forward. This was one of his last acts as governor.

Clearly, preserving natural lands against development is an ongoing battle against powerful forces. But city planners are implementing a powerful idea, which is working with and not against nature. Harness her forces. Now, as we reach a critical juncture in the era of radical climate change, we see the value of soft shorelines and acres of wetlands. Coastal marshes buffer the city against the ravages of hurricanes like Superstorm Sandy, which hit our shores in 2012. At the same time Christie was robbing the Meadowlands restoration fund, the Regional Plan Association, an urban planning institute that formed in 1922 expressly to shape the development of the New York City region, came out with their Fourth Regional Plan. One of its proposals is to turn the Meadowlands into a park, all of it transformed into a kind of expansive wetlands park large enough to act as a sponge as sea levels continue to rise and flood low-lying coastal lands. Sound far-fetched? Turning former military base Governors Island into a national park was proposed by the RPA in their Third Regional Plan, and before that, Gateway National Recreation Area was proposed in their Second Regional Plan. Both parks became reality.

New York Wetlands Reading List

McCully, Betsy. City at the Water’s Edge: A Natural History of New York (Rivergate/Rutgers, 2007).

Sullivan, Robert. The Meadowlands: Wilderness Adventures at the Edge of the City (Scribner, 1998).

Teal, John and Mildred. Life and Death of a Salt Marsh (1969) — a classic

Weiss, Judith and Carol A. Butler. Salt Marshes: A Natural and Unnatural History (Rutgers, 2009).

New York Wetlands Links

https://www.nycgovparks.org/parks/jamaica-bay-park/highlights/11326

Hudson River Foundation: https://www.hudsonriver.org/state-of-the-estuary

c. Betsy McCully 2018-2024