On a bright summer day, flying back home to New York, I look out the window to the landscape below as the jet descends toward Kennedy Airport. Ships like toy boats cut tiny white V’s through the blue water as they head toward New York Harbor. As we circle and bank toward the airport, I see Coney Island, where I used to walk its boardwalk and broad sandy beach. Blocky apartment buildings cluster along the edges, far more than when I lived there. We fly over Breezy Point, the sandy tip of Far Rockaway; its protected beach traces a long white strand against the blue. We descend toward Jamaica Bay, flying low over the Marine Park Bridge, over emerald green marsh islands and marsh-fringed tidal creeks. And as the plane lowers its wheels for the landing, I am reminded that Kennedy Airport was once called Idlewild, named for the marsh it was built on.

These blue and green and white spaces (and in winter, gold and silver) of water and marsh, scrubby dune and beach are mere bits and pieces of what once was. A single snapshot of a particular place in a particular time cannot reveal how the region’s habitats have been fragmented and altered, even erased over centuries. We need a time-lapse video to appreciate the magnitude of how we have changed the land.

Landscape ecologist Eric Sanderson in his book, Mannahatta (2009), reveals the New York landscape before 1609, when Hudson sailed into the harbor, in stunning images. The computer-modeled re-creations of Manhattan in 1609 are set side by side with aerial photos of Manhattan in 2009. Sanderson’s book and the Mannahatta Project of the Wildlife Conservation Society exhaustively document the flora, fauna, habitats, and topography of pre-colonial Manhattan based on old maps, drawings, narrative accounts, satellite images, and computer simulations. Habitats buried, erased, and forgotten are brought back to life, at least in the imagination.

Waters, wetlands, forests, grasslands, streams, ponds, beaches and dunes and maritime scrub — these were the dominant habitats in a patchwork mosaic. (Each of these can be broken down into smaller eco-communities—55 on pre-colonial Manhattan alone, as documented in Sanderson’s book.) When Hudson arrived on these shores, the landscape had already been altered, managed for millennia by the Indian dwellers in the land, the Lenapes. They used fire in controlled burns to create fields for their crops, maintain grasslands, and open up forests. Naturally, they cut down trees for fuel and building material. But there was a big difference in the way they used the land and its resources compared to what would come after European settlement. They did not engineer the land. They did not drain and fill in marshes and ponds and streams, or level hills, or build out shorelines with rubble to create new land. Such radical engineering of the land came with the Europeans.

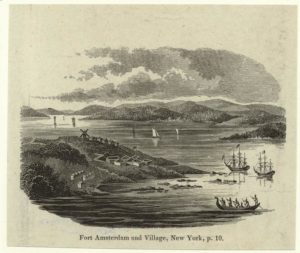

The Dutch were renowned for their technology and skills in reclaiming so-called “watery wastes” that in their eyes had to be drained, filled, and turned into cropland and pastures and villages and towns. They had done this to great success in the low-lying Netherlands. When they came to New Amsterdam (now New York), they set out to build a city on the water just as they had done in Amsterdam. Almost from the moment they arrived, they engineered the landscape. They drained marshes, filled in streams and ponds, leveled hills, and built out the shoreline on landfill. In doing so, they erased habitats that had supported plants and animals — including the human species — in an intricate, interdependent web of life.

In these pages I focus on four dominant habitats: marine waters and wetlands, woodlands, and grasslands. For each habitat, I provide an overview of how European settlers impacted it, how New Yorkers continued the process of degradation and destruction, and how we are trying to restore and preserve what is left.

New York Habitats Reading List

McCully, Betsy. City at the Water’s Edge: A Natural History of New York. Rivergate/Rutgers, 2007.

Sanderson, Eric. Mannahatta: A Natural History of New York City. New York: Abrams, 2009

New York Habitats Links

https://welikia.org (Eric Sanderson’s educational and research website)

c. Betsy McCully 2018-2024